US economic outlook after COVID-19: Top 10 takeaways

US economic outlook after COVID-19: Top 10 takeaways

October 21, 2021 | By Dean Sevin Yeltekin

Even for the most seasoned economists, predicting trends in the post-pandemic economy is a daunting task. Fortunately for those who attended the panel conversation I moderated during Meliora Weekend, two of my colleagues from the University of Rochester rose to the challenge.

Here are my top 10 takeaways from our conversation:

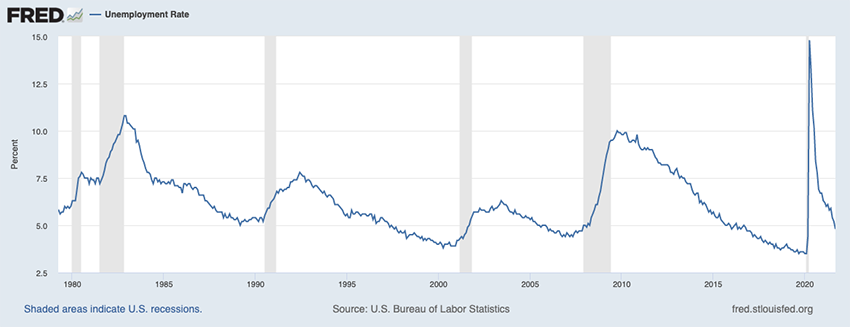

1. The COVID-19 recovery has gone surprisingly well . . .

The economy bounced back more quickly than expected from the COVID-19 recession, which lasted from February to April 2020. The unemployment rate rose from 4% in February to 14% at its peak before quickly falling back down within a matter of months. As of this writing, the unemployment rate stands at 4.8%. During the Great Recession of 2007-09, in comparison, it took six years for the unemployment rate to go from 10% to 5%.

2. . . . except for the unexpected rise in inflation.

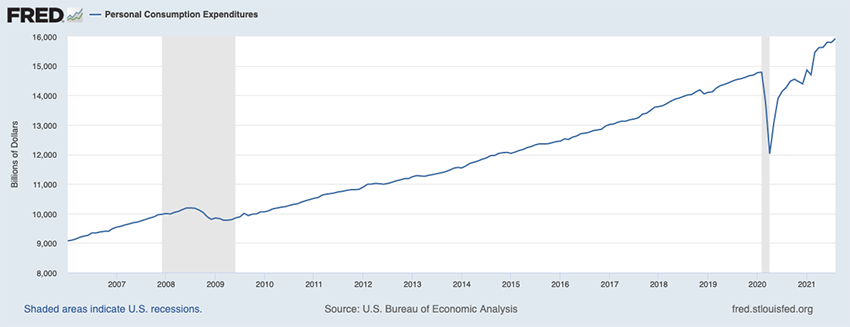

Economists have two hands so they can weigh the good and bad, Professor Kocherlakota pointed out. If most of the economic recovery indicators have been good, the bad is certainly the steady rise in inflation over the past year and a half. As I analyzed in a previous blog post, inflation increased 5.4% from June 2020 to June 2021, the largest 12-month rise since August 2008.

While Professors Kocherlakota and Smith agree that inflation will drop on its own as transitory factors like supply chain disruption and pent-up consumer demand resolve themselves, we can’t ignore the fact that the inflation rate is higher than it has been in 30 years. Even during the Great Recession, it never exceeded 2.0%. “If you asked me before the COVID-19 recession if I would ever see this kind of inflation again in my lifetime, I might have said no,” said Professor Kocherlakota.

Higher inflationary expectations come with profound consequences. The anticipation of higher future prices leads to higher current prices in long-term contracts, from employment contracts to supply agreements. Inflationary expectations also reduce the expected value of loan repayments, so lenders demand higher interest rates on loans. Once the inflation snowball begins to pick up speed, it’s hard to slow its momentum.

3. Higher interest rates could throw a major wrench in the recovery.

As of June 2020, the Fed predicted a 1.5% inflation rate by the end of 2021—well below its annual target of 2%. Clearly, that’s unlikely to happen. Currently, Federal Reserve officials are evenly split on whether or not to begin raising the federal funds rate as early as 2022. If inflation doesn’t fall below 3% in the coming year, we can expect that balance to shift.

While it may put a welcome drag on inflation, an interest rate hike could threaten economic recovery by slashing the demand for goods and services, which would stifle overall growth and new hiring. “We have lived through 20% interest rates before,” said Professor Smith. “No one wants to go back to that.”

4. The national debt has reached levels once believed to be unattainable . . .

Recent partisan brinkmanship over raising the debt ceiling has put the national debt back in the spotlight. Despite decades of doomsday predictions about the mounting level of debt,

red lines in the sand have turned out to be more arbitrary and less consequential than previously believed. Confident in the country’s ability to sustain greater levels of debt, the Biden administration is backing a proposed $1 trillion infrastructure bill and a $5 trillion social spending bill. Few expect the upward trend in spending to change anytime soon.

5. . . . but higher government spending may come with tradeoffs.

The well-worn cliché “There’s no such thing as a free lunch” holds true when it comes to government spending, says Professor Smith. In every society, total expenditures are divided between individuals, businesses, government entities, and foreigners. The more the government spends, the last productive capacity there is for other groups. In principle, the optimal level of government spending happens when society derives just as much benefit as it would from spending on other things.

Currently, Congress is enmeshed in a series of standoffs over the infrastructure and social spending bills championed by the Biden administration. “The critical aspect missing from these discussions is what individuals and businesses will have to give up because of this level of government spending,” said Professor Smith. He points out that governments only have three ways to pay for expenditures: taxation, borrowing, and printing money. Any borrowing by the government competes with borrowing by individuals and businesses, running the risk of crowding out private spending. And, when it comes to taxes levied to account for spending, consumers are left with lower disposable incomes.

6. Major tax hikes are likely to backfire.

The Biden administration will work with congressional allies to raise personal income taxes, corporate taxes, and estate taxes, starting with a 3% surcharge on incomes above $5 million. From Professor Smith’s perspective, those who project billions in additional tax revenue from imposing “soak the rich” taxes on the ultra-wealthy are headed for disappointment. The wealthier the American taxpayers, the more globally mobile they are, and the more resources they have to spend on lawyers who can exploit loopholes in the tax code.

7. The reason for the ongoing labor shortage isn’t entirely clear.

It only takes a quick drive around town to spot a dozen “Now Hiring” signs. The number of job openings hit 10.9 million in July, the highest since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking in 2000. David Autor, a top labor economist at MIT, recently examined the question of how the current labor shortage has developed for a recent op-ed published in the New York Times. “Research on this question is unambiguous,” he writes. “We don’t know what’s going on.”

Despite the popular perception that pandemic unemployment payments have discouraged people from looking for work, multiple analyses demonstrate otherwise. Another possible driver of the shortage, unreliable childcare, turned out to be insignificant as data demonstrates that women with children have returned to work as the same rate as women without children.

Professors Kocherlakota and Smith agree that the labor shortage may stem, in large part, from a shifting mindset. Workers are simply less willing to return to lower-wage jobs than they were before, and workers at all income levels are interested in more than a wage—they are concerned about factors like flexibility and safety at work.

8. The labor shortage isn’t translating into higher wages.

Despite the murkiness surrounding the root causes of the current labor shortage, one thing is clear: The shortage has yet to translate into significant wage growth. When adjusted for inflation, real average hourly earnings from September 2020 to September 2021 actually fell by 0.8%.

9. COVID-19 supply chain disruptions are changing the way businesses operate.

The business community never saw COVID-19 coming. In manufacturing, the just-in-time (JIT) system that minimizes inventory and maximizes efficiency backfired when the pandemic sent shock waves through supply chains on a global scale. Bottlenecks and shortages of critical parts, such as computer chips used in the auto industry, have exposed the risk of having few suppliers and low inventory. Ultimately, there will always be a tension between being lean and efficient, on one hand, and being flexible enough to be resilient, on the other. In the wake of the pandemic, the pendulum will swing away from lean operations toward resiliency, at least for a few years.

10. The Federal Reserve is moving toward creating its own digital currency.

“When I left the Fed in 2015, digital currency was still very much a novelty,” said Professor Kocherlakota. “That is no longer the case.” At this stage, Bitcoin and other types of digital currency are primarily used as a store of value, not a transaction device. As that ratio changes, the Fed will have a strong interest in devising its own digital currency. This central bank digital currency will also alleviate the concerns of policymakers about the long-term reliability of stable coins, which can be exchanged for a fixed unit of U.S. currency. As digital currency moves into the mainstream, all eyes are on the Fed to respond.

To watch the panel conversation, click here.

Sevin Yeltekin, Dean

October 21, 2021

Narayana Kocherlakota is the Lionel W. McKenzie Professor of Economics at the University of Rochester. He served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from 2009-2015.

Cliff Smith is the Louise and Henry Epstein Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Finance at Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.